Things happen to people, and people make music. Therefore, there will always be a connection, conscious or unconscious, between the two. The musical material itself is revealing in this regard and the significance or connection doesn’t need to fit into what can be articulated. It was reaffirming to hear these views echoed by Brooklyn-based composer, improviser and performer Lucie Vítková when we discussed their upcoming album, Aging, which will be released May 14 on Infrequent Seams.

I’ve been lucky enough to be programmed alongside Lucie (pronounced LOO-tsi-yeh) a few times now, thanks to performances by S.E.M. Ensemble and its corresponding festival Ostrava Center for New Music in the Czech Republic. Attending Ostrava in 2019 introduced me to long-time S.E.M. collaborators Lucie and bassist/composer James Ilgenfritz, who runs Infrequent Seams (and released my album). Lucie and James first met at the 2013 Ostrava Days Festival, a highlight of which was their performance with composer and visual artist Charlemagne Palestine. I’m captivated by Lucie’s works, which often create and stay in a space with that sought after balance; a degree of unpredictability while maintaining cohesiveness. Aging is no exception.

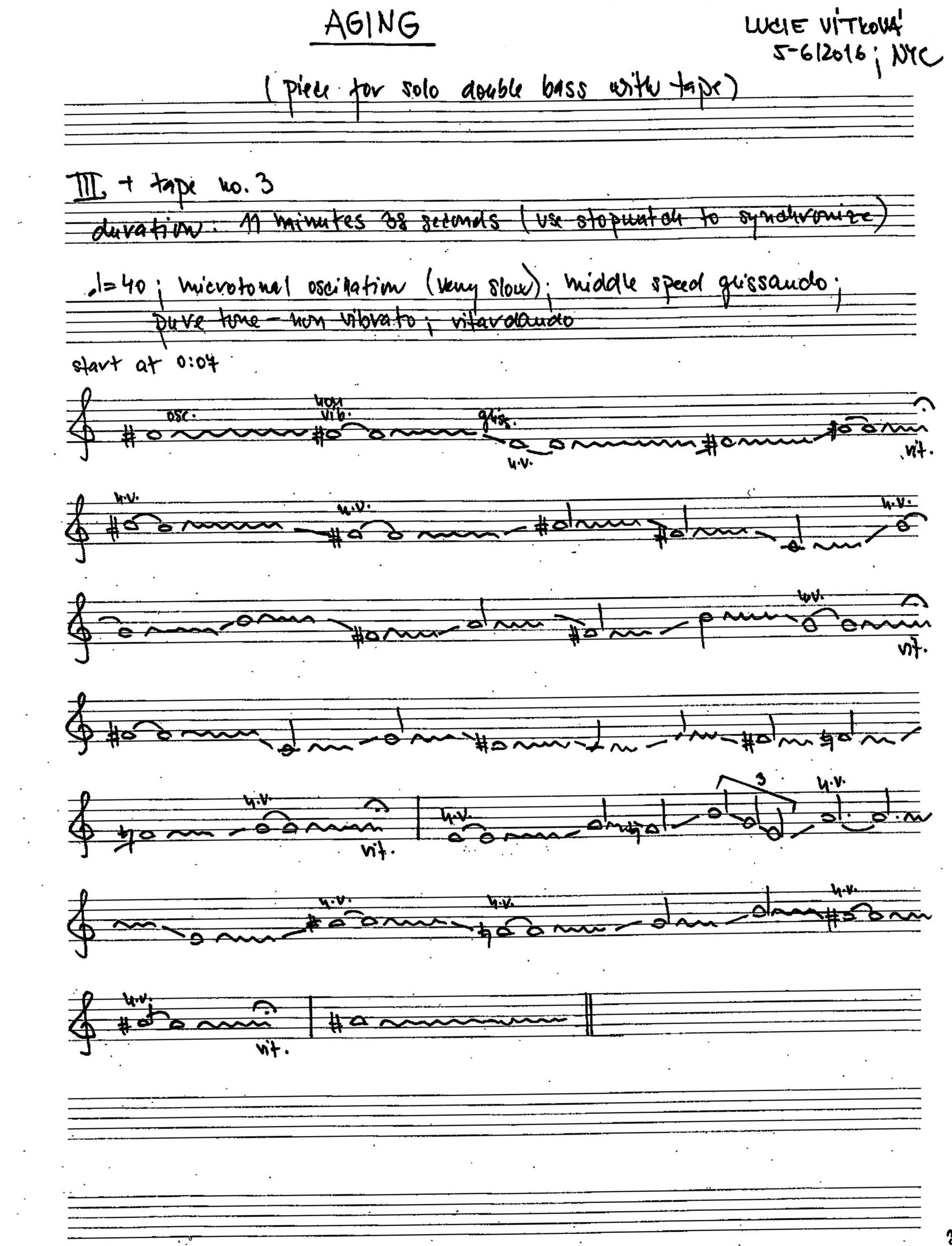

The album, Aging, is composed of seven compositions of the same name, which are labeled I through VII. The series was composed in seven parts so that bassist James Ilgenfritz could choose his favorite of the set. “Working hard is always on my mind,” says Lucie. “Just for the experience of a performer having the possibility of choice, maybe I can work harder. (laughs) He can play different ones he chooses or have one favorite and the rest will be kind of there as an option.”

The musical material originates from Lucie’s first solo instrumental work, a ten-minute solo bass piece in seven short cycles written while studying in Brno back in 2009. The material from the 2009 composition was electronically stretched eight-fold to generate the material for Aging. Lucie says, “The music is aging and my taste is aging as well. When I stretched the music from 2009 eight times and filtered it in my computer it got closer to my taste. In 2009, my ideas were already good; I wanted to work with that material and be in touch with it. I decided to rewrite these slowed-down sound scores for James and I was imagining we would use preparations for the bass to get closer to the electronic track.”

Given the abundance of music that Lucie wrote, they decided to record the set as a 75-minute album. A sentiment that’s been on my mind of late is that the longer a work is, the less musical material you need. The inverse also holds, in a shorter work you have the flexibility of throwing many ideas into a piece without it hobbling across the finish line in an incohesive state.

Looking at the score of Aging, it’s striking to see 75-minutes of music laid out on a mere seven pages. I shared with Lucie my experience of the work as one space, which constantly guides your ear to shifting details. “I agree, it’s one space,” said Lucie. “During the whole album, you can really be switching between similarity and difference. I’m putting my way of perception into the music. So I’m thinking, ‘wow these things are really similar, but if you look closer they are really different as well’. In this album, it’s especially true. There is only bass and electronics for 75-minutes, that makes it similar enough. But little details…and each part has its own thing.”

One not so little detail is the surprising presence of consonances, a rare occurrence in Lucie’s music, that slide in and out of view prominently in Aging III. “The original piece is pretty consonant, the way I perceived time back then was much quicker. I was already using microtonal oscillations, which I’ve been using since...except perhaps I give it a bigger space now. In the 2009 piece, there was a large focus on a playful melody. I don’t know that I do so many melodies these days! (laughs) The techniques used in the 2016 work were used to blur the melody, to get under the surface. Because melody, for me, is a way to stay on the surface. I wanted to go deep into vibration. In III there is this unexpected slow melody, very simple, but suddenly it starts to melt through the microtonal oscillations.”

Whatever was originally playful in the 2009 composition has been sufficiently melted in Aging. I use the word “melt” again as it points to another key musical element in this work, the sliding. I wondered if this recurring element in Lucie’s music (I’m specifically thinking of the sliding in their string quartet Nine) was linked to their practice as an accordionist. Turns out, it stems from their vocal practice. “The longer glissandi are connected to voice and the way I feel my vocal cords. I use my voice to blur the keys of the accordion so that I always match the timbre of my voice to the timbre of my accordion. I go into beatings and blur the keys, which are too rigid,” says Lucie.

But the accordion naturally plays a vital role in how Lucie perceives sound. “I think the thing I have from accordion is the non-vibrato sound. I always want that, from string players especially. There’s this almost string midi sound in my head that I want to hear,” says Lucie. “The way I want people to play strings is to always stop the bow on the string. This is from the bowing of the accordion because I just stop or turn the bellow. I was telling this to James a lot because I can hear it in the sound. I can hear if you lift the bow up from the string, it’s a very specific sound. I just want it to stop without any accent. It is very natural for me. I love the sound and the discontinuity of it.”

This left me with a smile on my face. Stopping the bow on the string without lifting it goes against everything classical string players are trained to do. It is a completely reasonable request to not lift the bow and simply needs to be unprogrammed with intentional practice. But close your eyes and picture for a moment an orchestra that has just rang out the final chord of a symphony. Where are their bows? In the air! To put it another way, the shame that would be brought upon a string player in a conservatory masterclass who simply halted their bow at the end of a phrase is simply unfathomable.

Now I’m sure that there are other composers that also ask for this, but I like that Lucie insists on it. It requires a performer to physically embody Lucie’s sound world. “Usually when people move while playing, it is an added choreography next to the music they play. So I always need to see if the choreography that they’re doing to my piece actually generates the sound that I want,” says Lucie. “As you said, you learn the circle movement to lift up the bow and it is related to a specific sound. Maybe it’s good for classical repertoire but my music has its own movements. Sometimes when people are on the stage they start to perform movement and it starts to be in dissonance with the music they are playing. I always try to say, ‘You don’t need to move as much. It’s actually taking attention away from the thing that we are looking at.’ I want close attention to be paid to the music. We just need to see what we are doing, not to perform what we are doing.”

The goal of creating a performance situation that lends itself to focus on the music extends itself to Lucie’s treatment of electronics. “I sometimes feel that if you use electronic instruments they either accompany the acoustic instruments or they take over the place,” says Lucie. “I wanted to have a situation where they were in each other’s company. Onstage, there is only one speaker placed next to James, so they are like two entities, they have equal positions on the stage and equal roles. There’s not this accompanying or leading.”

On the recording we can’t experience the bass and electronics onstage as two separate entities, but that image changes how I hear it. The completion of the recording is of course a huge milestone and since the work was originally written in 2016 from material dating back to 2009, it serves as a starting point for reflection. Lucie says, “I had a period in my life when I was looking at this person in the past like, ‘oh my god, it’s so embarrassing’. But I think I’m aging into an appreciation of this person. I love that with aging I can get a bit calmer, I don’t have to have this high energy all the time which is exhausting in some way. You have these highs, but also you have these lows. Living like that, in this polarity, is really demanding. It sometimes kicks in, but I don’t get as excited anymore, so I’m less exhausted. I can calmly enjoy days passing. In 2016, I was also a very different person. It was very new coming to New York for me and studying at Columbia. You know I finished my PhD?”

I didn’t and gave my congratulations, as that is a huge deal! “It’s a very new period in my life, I’ve never been out of school. For the first time I’m looking for jobs and seeing where to go from this place,” says Lucie. “It’s very different, thinking of myself as a teacher possibly. I’m gathering knowledge and giving it shape so I can share it with other people. This is my aging going through different stages. I think another big before and after is when my mom died, which was eight years ago. I’m always fantasizing about the life I could have had if they were still here and thinking about the life I have to live when they're gone. I think that was a big influence on who I am now. These are huge things, which we can’t divide from music because people make music and things happen to people. There always has to be some connection with it. I still am not sure which concrete things it’s changed. I think lately, I’m wondering about the young person, the before. It was a very different energy. I’m wondering about this person, and what they would do. But it’s just me here now, which is fine as well.”

There doesn’t have to be a concrete tie that can be articulated between musical material and the things that happen to people. But having this added context to the pieces, one thought struck me in connection to the musical material. Each movement, or “vignette”, is similar on the surface level. But the little details...when you get deep into the sound itself they are part of one whole but are in fact very different. So, yes, the Aging pieces could be seen as musical self-portraits of Lucie at different frames of their life. But they could also be stand-ins for the imagined aging of this other person who now only exists in that “before”. In both scenarios, there’s reason for the blur.