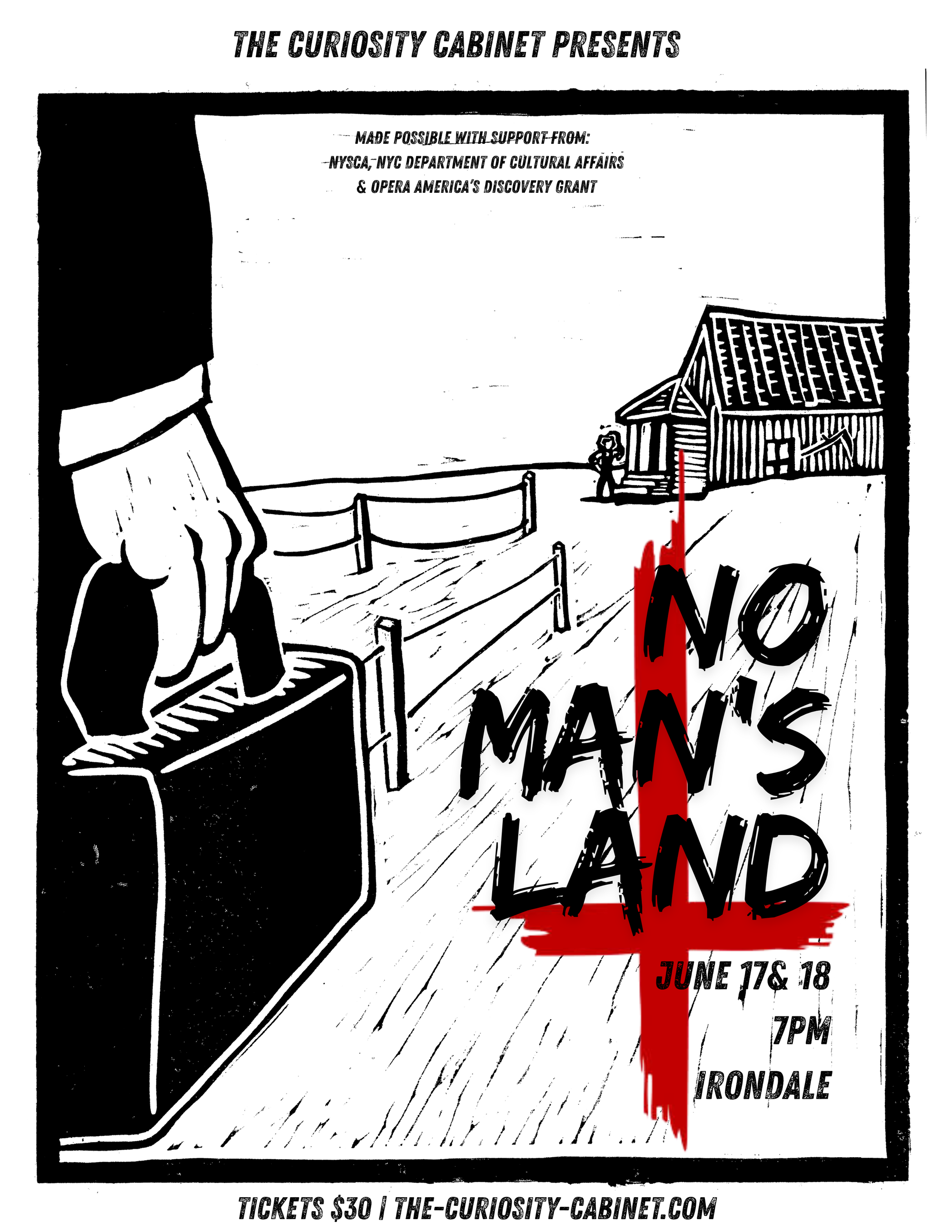

Deals with the devil, a golden locket, and endless rain amid one of the greatest American man-made ecological catastrophes. Composer-conductor and now director Whitney George's two-act opera No Man's Land, with libretto by Brittany Goodwin, makes its world-premiere at Irondale in Brooklyn from June 17-18.

No Man's Land is scored for a cast of 10, a small chorus, and an instrumental ensemble of seven. The production is being presented by The Curiosity Cabinet – a collective founded by Whitney George in 2009. Rehearsals are in full-swing – and I'm grateful to be in the room for this moving and gut-wrenching opera as Whitney's assistant conductor. I'm learning so much from Whitney, the singers, spending quality time with the score, observing rehearsals, and of course podium time is invaluable as conducting is new for me.

Whitney George's approach embodies what is possible on the other side of your comfort zone. I'm so inspired by what she's built with Curiosity Cabinet and No Man's Land – a beast of an opera, massive creative world, contemporary and visionary production, warm working environment, musical community, penchant for responsible risk-taking – all with a small 501(c)(3) with a modest production budget. I hope you get to see it too.

Anna Heflin: We just wrapped up music rehearsals for Act 1 and are moving on to staging rehearsals. You weave character development into the music rehearsals and I’m observing how you have a “yes and” approach to character motivation by giving them enough information to get the imagination spinning. With character development, how do you balance specificity with leaving interpretive space for the singers to make the characters their own?

Whitney George: I think a lot about how much information you give, and when. In the first initial rehearsals, I do try to let the music speak for itself. While I’m composing, try to imagine that the music is the ONLY thing that’s carrying the drama, and for that reason, that staging is really an “icing on the cake”—I would hope that it would be just as compelling without any staging at all—that an audio recording would be just as fascinating to listen to. People have described my music as incredibly visual—and I take it as a compliment.

It's important for me not to dictate every moment for the singers embodying these roles. I'm a strong believer that everyone has their area of expertise, and being overly controlling restricts the space for others to contribute their insights. One of the most exciting aspects of this process has been intentionally leaving open spaces for singers to bring in new ideas or interpretations I might not have initially considered. When creating a new work, there will inevitably be gaps or points needing clarity, and allowing singers to highlight and address these gaps is crucial to our collaborative effort.

To draw a parallel outside of music, it's like going to a hairdresser. Though my options have changed since cutting my hair short, I used to trust my hairstylist completely to choose the style. This trust requires confidence in their expertise: they understand face shape, hair texture, and how various cuts might flatter an individual, considerations I may overlook if I simply choose a trendy style. Similarly, trusting my tattoo artists has been essential. Had they strictly executed my original ideas, my tattoos probably wouldn't look as cohesive or appealing. Artists consider the tattoo’s size, aging, placement, and how it integrates with existing or future artwork.

Though these examples may seem tangential, the principle translates directly to my musical process. I come prepared with detailed ideas and clear directions, but deliberately keep certain aspects open-ended. This approach encourages singers to explore and define their characters meaningfully, informed by both the music and text. Consequently, the cast becomes more deeply invested in the creative outcome.

The initial interpretation of a new work is inherently intimidating since no prior blueprint exists. It's thrilling to lead this first interpretation, particularly because I influence the process through composition, conducting, and directing. As producer, I also strive to foster collaboration across all facets essential to an opera—art direction, scenic and projection design, lighting, and more. While maintaining control is crucial, balancing this with openness allows each expert to meaningfully contribute, ultimately enriching the entire production.

AH: The score is massive. It’s 2+ hours of music with 10 cast members, a small chorus, and chamber ensemble. I’m wondering where you started and how you managed the flow of the movements between the densest musical moments (like the opening scene), arias, and scenes that we can confidently call the bops like "The Plague is on the Plains".

WG: I wish I could say that I began the opera at the beginning and had the libretto fully prepared, but new works rarely unfold that way, often due to funding and grant opportunities. This opera is supported by the Discovery Grant, which is significant for me, as I've applied several times before. I'm open about past rejections—like with Fizz and Ginger, which, despite being denied at the final stages, had a successful run at the New York Comedy Club in 2023 and later at Chicago Fringe. Grant decisions often depend on adjudicators' specific agendas, and earlier rejections never deterred me; persistence is essential.

When applying for the Discovery Grant for this opera, my librettist and I strategically created work samples from moments we anticipated being impactful. These included the initial hoedown from Act 1, Scene 1, a key aria known as the "Locket Aria" from Act 1, Scene 7, and the dramatic Act 1 finale featuring the devil’s aria. Specific roles were written with performers already in mind, notably Shane Brown, who has been central in many of my projects from Princess Maleine to the radio dramas.

Due to scheduling conflicts, casting shifted during development, but having specific singers in mind initially helped solidify early proofs of concept. The writing process was somewhat nonlinear. After securing funding, I had to navigate writing scenes from different parts of the opera simultaneously, based on when the libretto sections became available. This presented a considerable challenge, as composers generally prefer to start from the beginning or follow a more logical sequence.

Nevertheless, I embraced the challenge, composing initially the middle and end sections of Act 1 and the beginning of Act 2. Subsequent scenes filled out progressively as the libretto developed. The penultimate scene of Act 1, Scene 10—a major family drama—came next, after which I could finally return and sequentially tackle the opera’s opening.

Collaboration with the librettist involved significant back-and-forth dialogue. Scene 5 of Act 1, "The First Storm," required a complete rewrite to maintain thematic coherence within the opera. After Act 1's completion, thorough reviews and MIDI playbacks were crucial to ensuring smooth narrative and musical continuity. Hearing the music performed by actual singers has proven far superior to MIDI alone.

My composing approach involves disciplined daily sessions, typically in the morning, over coffee. Each session ends with exporting a PDF of my progress, ensuring no work is lost due to file corruption—a precaution that, fortunately, hasn't yet been necessary.

Most of the opera initially emerged as a piano-vocal reduction, always with violin lines prominently in mind due to their orchestral importance. I ultimately chose a seven-piece ensemble inspired by Stravinsky’s The Soldier’s Tale, substituting trumpet with flute for practical reasons. Certain sections, notably the "Rabbit Hunt" in Act 2, were directly written for full ensemble before creating a piano-vocal version. This orchestral thinking is often apparent in the final reduction, distinguishing those sections originally intended for a fuller texture.

AH: Violinist Adam von Hausen, who you’ve worked with for years, has a special character role in connection with the Devil in the production. The music is crunchy, folky, and sinister. What was in your ears for the violin line and how did years of collaboration with Adam feed into this part?

WG: There are numerous musical works that connect the devil to the human soul, often symbolized by the violin. The violin’s shape, curved and human-like—perhaps even feminine—reinforces this symbolism. Given the devil's significant role in my opera, No Man's Land, I was particularly influenced by Stravinsky’s The Soldier’s Tale, reflected in the instrumentation I've chosen: flute, clarinet, trombone, violin, double bass, piano, and percussion. Unlike Stravinsky’s original ensemble, I replaced the trumpet with a flute and its related instruments (alto flute, bass flute, piccolo) for greater versatility, although at times I did miss having an additional brass voice to emphasize powerful moments involving the devil.

Even before finalizing the ensemble, I knew the violin would play a crucial role dramatically. Early on, I envisioned a scene where the devil would physically bring the violin out of the instrumental group and onto the stage. This idea reflects my philosophy that instrumentalists are just as integral to storytelling as vocalists. I strongly oppose hiding musicians in an orchestra pit, believing their visibility enhances the narrative impact.

This belief guided our choice of Irondale as the performance venue. Its distressed, fresco-like atmosphere was perfect for the opera's aesthetic. Initially considered for Chasing Light, our 2023 sensory-focused work, Irondale was ultimately reserved for No Man's Land, while Chasing Light moved to a black box theater to accommodate extensive use of fog machines.

Incorporating the violin prominently from the beginning was natural, with many early drafts written specifically for piano, voice, and violin. For future productions, while a piano-only reduction is possible, the inclusion of violin significantly enriches the work.

My personal relationship with musicians shapes my composition process. Adam, our violinist, has collaborated with me for nearly a decade, profoundly influencing my writing. His extraordinary dedication and skill were particularly evident during the Extinction Series, for which he memorized 40 minutes of solo violin music I composed specifically for him. Such collaborative relationships highlight that composers depend greatly on musicians to realize their artistic visions.

I'm inspired by similar historical partnerships, like Morton Feldman’s The Viola in My Life, written expressly for a particular violist. Too often, musicology isolates music from the composer’s personal experience, an approach I find shortsighted. Personal experiences inevitably shape creative output, and this is no less true in my own compositions.

Ultimately, including the violin as a core element pays homage to significant 20th-century influences like Stravinsky and acknowledges the profound collaborative relationship I have with Adam. The violin's integration into the narrative, directly interacting with the devil and transcending conventional stage boundaries, promises a powerful and exciting dramatic experience.

AH: I’m of the opinion that learning by doing is the way to grow and am so grateful to be your assistant conductor on this project. I’ve worked conducting into my doctorate at USC Thornton as an elective field, studying with Professor Larry Livingston, but podium time like what I’m experiencing with you in No Man’s Land is a huge opportunity that most new conductors don’t get. How did you learn to conduct and what inspired you to do so?

WG: I often describe myself as a "duct tape conductor," meaning my approach might not always be elegant or technically flawless, but I consistently get the job done. This practicality emerged from necessity early in my musical education. My first experience conducting was in an undergraduate class, conducting the Intermezzo from Holst's Suite in E-flat with a large wind ensemble—an intimidating challenge for a sophomore whose previous practice had been limited to mirrors. That early experience underscored how essential real-world podium time is for developing conducting skills.

Conducting isn't merely about perfect technique; it must also adapt to the ensemble's needs. A sophisticated, polished approach might suit the New York Philharmonic but isn't always effective with younger or less experienced groups. Conducting young musicians or beginners is often more demanding because they require clarity and simplicity.

I'll never forget the feedback from my first conducting final, when the band director told me, "You conduct like a girl." Despite the unhelpful and offensive nature of that comment, it didn't deter me. Instead, I pursued conducting even more seriously after transferring from California State University, Chico, to CalArts, a school known for fostering interdisciplinary collaboration.

My time at CalArts significantly shaped my creative and conducting practices. Early collaborations there pushed me to take the podium more frequently. A memorable project involved composing for clarinet, strings, percussion, and a dancer, where practical difficulties with the ensemble required me to step up as conductor. Positive reception to that performance encouraged further projects with larger ensembles.

Continuing into graduate studies at Brooklyn College, I conducted Ursula Oppens’ Contempo Ensemble, immersing myself in challenging contemporary repertoire. Conducting this demanding music significantly developed my skills, particularly with complex rhythms and mixed meters. My master’s thesis, a setting of The Yellow Wallpaper, intentionally featured irregular, asymmetrical rhythmic structures as personal challenges to improve my conducting abilities.

As my conducting opportunities expanded, particularly in contemporary opera, I found myself regularly engaging with living composers. My own compositional experience allowed me to offer practical feedback on scores, helping composers refine their works through suggestions on voicing, engraving, and rhythmic clarity—insights I gained from troubleshooting my own compositions.

Ultimately, clarity and effectiveness guide my conducting style. While looking elegant on the podium is desirable, my primary goal is always clear communication to support performers’ artistry. I greatly admire conductors like Pierre Boulez, whose precise, transparent technique leaves no ambiguity, setting an example I strive to follow in my conducting career.

AH: So the big reason why you have me as your assistant conductor for this production is because you’re staging the opera with director Attilio Rigotti – which is a new thing for you – and you physically can’t be in two places at once during staging rehearsals. What is your broad directorial vision and how are you approaching this new skill set? Is stage directing something you wanted to try your hand at for a while or did it speak to you specifically for No Man’s Land?

WG: Much like my experience with conducting, my role as stage director arose from necessity. Initially, we had a director lined up, but she withdrew unexpectedly. At that point, I had to choose whether to bring in a younger stage director or hire an assistant conductor and handle staging myself. I chose the latter because I had a specific director in mind, Attilio, who wasn't available for our full production schedule. Given our tight timeline—The Curiosity Cabinet plans productions and casts early to secure specific performers—I decided to step into the directorial role myself.

Once committed to directing, I felt nervous but also realized that it might not be as daunting as I initially feared. My compositional process already involved considerable thought about stage positions, entrances, exits, and physicality. Reflecting on my training at CalArts, where I regularly integrated choreography and stage movement into musical performances, I realized I had already exercised some of these directorial skills.

Our first staging rehearsal, especially given the complexity and size of Act One, was challenging yet rewarding. Despite initial apprehensions, we accomplished a great deal. This experience boosted my confidence significantly, making me genuinely excited for our upcoming Act Two rehearsal.

Looking ahead, I don’t necessarily foresee giving up conducting entirely for directing, but I would certainly consider directing another opera if the conducting position wasn't available. Moreover, I'd be very open to repeating this experience in future productions—hiring an assistant conductor while taking on the directing role myself.

Ultimately, seizing unexpected opportunities is vital. It's disappointing when people don’t rise to the occasion because embracing challenges wholeheartedly is essential for personal growth. The positive outcome of my directing experience is largely due to our cast's exceptional preparation and dedication. Despite initial production hurdles, constraints often spark creativity, and directing this opera has proven to be a perfect example of that.

AH: There’s an inevitability about the story of this opera and its setting of a Faustian bargain with the devil in the landscape of the Dust Bowl during the 1930’s. Can you talk about the contemporary implications embedded in the story of the Dust Bowl?

WG: The climate crisis and human complicity in the effects of climate change is one of my central artistic and compositional pillars. I have many pieces/projects centered on this theme. As the Artistic Director of The Curiosity Cabinet, I have made “The Extinction Series” a programming staple in our season for three years now. The Extinction Series is a collection of musical eulogies to species who have sadly become extinct due to man’s pervasive presence and infringement on their natural habitat. No Man’s Land is a continuation of this thematic programming, seeing as the Dust Bowl is the largest man-made climate crisis in our history. Given our current geopolitical climate and the ongoing denial and erasure of climate change, I felt it tremendously important to compose a cautionary tale to effectively remind us all of the dangers of repeating history.

AH: I feel it’s the responsibility of composers and conductors to make their collaborators feel taken care of – and creating a rigorous, caring, and playful environment imbued with trust is a tall order in a project this ambitious. First and foremost, I think this is a character attribute that you just have and you motivate others naturally through this energy. But there are thoughtful actionable items like having wonderful food for the cast during long rehearsals, celebrating cast member birthdays, and working with artists over long periods that could be applied by others in the field. First, what are the artistic benefits of curating a thoughtful collaborative environment? If you were speaking with someone who is more used to a traditional operatic rehearsal process what small steps might you recommend?

WG: I've often mentioned in rehearsal that nothing good happens on an empty stomach or without sufficient sleep and hydration. My biggest personal challenge might be drinking enough water! Taking care of performers is central to my philosophy; snacks and meals during rehearsals, especially those extending over mealtimes, are essential. Given that we're a small 501(c)(3) with a modest production budget, I believe funds should not force performers into rushed, uncomfortable meal breaks between rehearsals. Therefore, providing home-cooked meals during rehearsals, which typically start in the afternoon at my home, feels both practical and respectful.

Ensuring performers feel valued and supported is critical. These artists invest significant time and energy into breathing life into my work, and reciprocating their commitment with care and generosity is fundamental. We begin our production process with an ensemble dinner, fostering camaraderie and building a strong team dynamic. This year, our bonding included a square dancing session, which was not only practical for rehearsing the opera’s hoedown scene but also genuinely enjoyable.

Additionally, we hold dramatic libretto readings to facilitate discussions about plot points and character development. Building connections among cast and crew before rehearsals intensify ensures better collaborative dynamics throughout the production. I'm particularly fortunate to have my husband actively involved in this process; his commitment matches mine in bringing these projects to life, highlighting how mutual support strengthens our overall endeavor.

I firmly believe in treating people with generosity and respect because this kindness invariably returns. Surprisingly, such fundamental care is not universally practiced, which is unfortunate. I'm intentional about modeling this approach.

Aligned with our ensemble's mission to challenge classical music's inherent classism and elitism, we have lowered ticket prices this season from $40, recognizing many of our supporters and audience members—often fellow artists—are economically strained. Despite inflationary pressures, this year's production dedicated 60% of the total budget directly to artist fees, the highest proportion in our history. My aspiration is to further increase this percentage, ideally reaching 70%, reducing our reliance on expensive venue rentals to maximize compensation for the artists who make our work possible.

Ultimately, my guiding principle is clear: put into the world the generosity and loyalty you wish to receive. By consistently treating people well and prioritizing their needs, I hope to cultivate lasting relationships and mutual respect, a goal already bearing fruit within our ensemble.